When we sit down in Molly Dyson’s bedroom-cum-studio, the illustrator and artist is waxing lyrical about her favourite topic- her occasional portrait subject, and constant companion, the dachshund-cross-chihuahua, Chippy. “Her armpits and her bottom lip are my favourite bits about her,” she says, as she nuzzles her freckled nose into the small threadbare patch of Chippy’s belly. The little dog lolls gleefully on Molly’s lap, as her stubby legs paw the empty air.

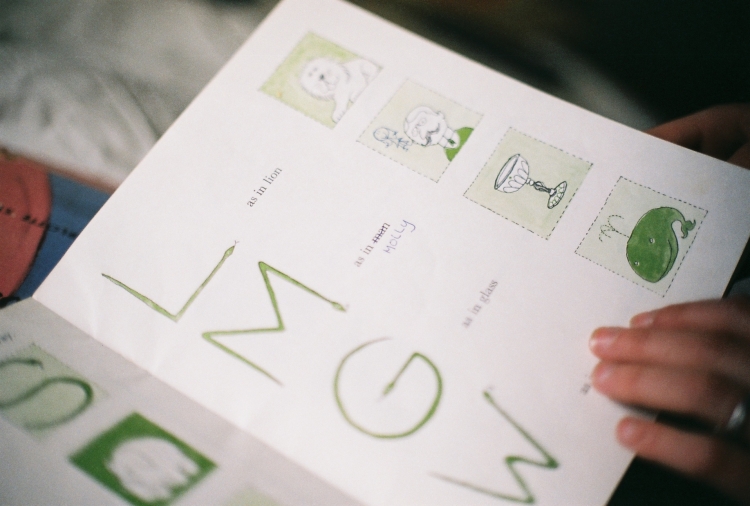

Molly graduated the VCA in 2010 where she completed a Fine Arts degree, majoring in drawing. She has since been focusing less on her artistic practice, and more on her work as an illustrator, creating designs for independent Melbourne stores such as Five Buroughs.

She is still in the process of trialling different ways of drawing, to find a style that best captures her personal fingerprint.

“I don’t think that I’ve really started to create characters yet,” she says. “I think I’ve been feeling my way through how to draw people.”

Her illustrations teem with bold colour, playful shapes, and clean lines. Rounded bodies of dogs, children, men and women rendered in washes of candy pink, sapphire blue, and vibrant green, bob like balloons throughout her compositions. Their features are sketched in fine black ink; their small eyes pitched aloft, or cast in furtive, sidelong glances to one another. While her drawings have a strong colour pallet, she is still not sure of exactly of how she wants to express her characters’ anatomy; which details she wants to “amp up,” and which she wants to diminish.

“When I look at all sorts of illustrators I look at the way that they draw eyes. Quentin Blake does dots, and Anna Walker also does, and I think, why the dot? Or do you do something that’s more googly and stylised?”

“I’m still feeling my away around that,” she says.

Towards the end of her Fine Art degree Molly’s main focus was on colour. Along with her illustration work she also completes collages, composed from her hoards of collected clippings from old magazines.

“I think the collage work is often about colour and texture and ways of dealing with those.” She sees them as a continuation of her painted colour studies.

In 2011, she and fellow Melbourne artist, Fiona Waters, held an exhibition entitled Small Goods, at Seventh Gallery. The show featured both watercolour pieces and sculptural works. Her watercolours conveyed inconsequential objects, and throwaway commercial items truncated into uniform thumbnails, and presented in an archival order.

“I was thinking about packaging, and detritus, and this weird little selection of things that just get left behind on your mantle or on your coffee table.”

“The scale of these things means they get overlooked because you don’t worry too much about the space that they’re taking up,” she says. “But they’ve all come from somewhere and they all have a little purpose, and the purpose isn’t always realised.”

Her works also featured representations of logos she extracted from packaging, and fabric design. She was interested in transforming these from commercial emblems into artistic motifs. They are painted with the same formal simplicity and bright purity of tone she brings her illustrative works.

“I think that my stylised approach to illustration feeds from this,” she says, “Given a brief I would use these same aesthetic qualities.”

Transitioning from fine art to illustration was something that made sense for her to do.

“I started off at the VCA not really understanding what I wanted to do or what I wanted to make,” she says. “Once I’d finished it started to make sense that I would feel more comfortable working as an illustrator.”

At first, she sought to split her illustrative practice completely from her art. However, the more she worked in this way the more she realized that her work was not “one or the other.”

“If I were to approach my work from an art angle, for an exhibition, I would probably be investigating ideas about illustration, and how illustrations are made within certain guidelines, or within a brief, as the artwork,” she says, “I look at a lot of other people’s illustrations as art.”

Thus her artistic projects and her illustrative ones are indelibly entwined.

“I don’t think there is any separating them, and once I realised that I felt freer than I’ve ever felt making things.”

This newfound freedom defines her current practice, which is articulated through a series of thorough trials and experimentation. “I haven’t been setting myself many guidelines other than just to figure out how I want to make images.”

She is currently working towards formulating a more consistent approach to her illustration work.

“The beginning is always the most difficult thing,” she says. “It takes me quite a long time to formulate a process.”

Generally, she will start by looking to other artists and designers, to see how they have dealt with representing the same subject matter. She is interested to know “what aspects of other things that have already been created I like, and how I would go about achieving the same solution,” she says, “what someone else has previously done in a way that takes Problem X to Solution Z.”

She then begins an arduous series of practise sketches. “First I will basically sit down and sketch out what I have in mind and then I re-sketch that again, and I re-sketch that again,” she says.

Her simple tests become “more elaborate as they go along.”

Since she comes from a Fine Arts background and has limited formal design training, Molly sometimes “feels like a fraud” within the industry. However, as an avid reader of design theory, and diligent collator of source material, Molly has taken it upon herself to learn about and reflect upon a variety of design histories and traditions.

Molly lived in Berlin for nine months last year. Around this time she found herself becoming more aware of cultural nuances in illustration and design styles.

“When I spent a lot of time in Berlin I started drawing buildings really differently, and that was a revelation to me,” she says.

“I guess I had seen a lot of four stories buildings with repetitive windows and doorways and balconettes, in European illustrations,” she says. Living there, and seeing the architecture in real-life, she became aware of this signature element being sourced from a real spacial reality.

When she returned to Australia she had a renewed awareness and appreciation for the idiosyncratic character of our architecture, and the potential for relaying these quirks through illustration. “I have really enjoyed coming back and trying to draw buildings that mean a lot to me.”

Molly has lived in the Western suburbs for most of her twenty-three years, growing up in Seddon. She feels a particular affinity for Footscray. Returning there after living abroad was an eye-opening experience.

“Going through Footscray I had this sudden feeling that I wanted to draw all these signs on top of the butchers in the Footscray market,” she says. “They all have these really different little logos of pigs in little dresses dancing, and pigs wearing wigs and lipstick, and little sheep posing.”

“And I realized that that isn’t everywhere.”

Her most recent design job was the creation of a tea towel and coffee cup design for Five Buroughs. The designs feature landmarks from the Brunswick landscape, configured into a stylised street scape. She created a plethora of watercolour illustrations of landmarks, trees, characters and signposts from around Brunswick, and scanned these digitally, before assembling them into a pattern.

“When I started the project, I tried doing lots of different things, and then pulling them all together and seeing what worked, and then I’d go back and repeat, and pull that together again, and it was a back and forth until finally I came up with a process that worked, and that could be applied to all the aspects of the project.”

The design brief, by its nature, is always essentially asking a question. The trick, she thinks, is answering it with “your own spin.”

Her spin, or “fingerprint” as she calls it, is what she is most interested in figuring out.

“I feel like I haven’t really found that yet, and that’s why the process is so difficult.”

Her process is more or less a roundabout way of prodding her signature to emerge.

“Every brief you’re given, you kind of feel your way through it and then by the end you realise, this is my spin on it. “

These small epiphanies that occur along the way may help her to streamline future projects.

“The more I realise these connections, it’s like learning to see.”

Each project allows her a fuller understanding and, thus, a better command of her way of working.

“I feel like it’s a revelation every time I realise things like that, and I think, yes! I get it! This is good!”

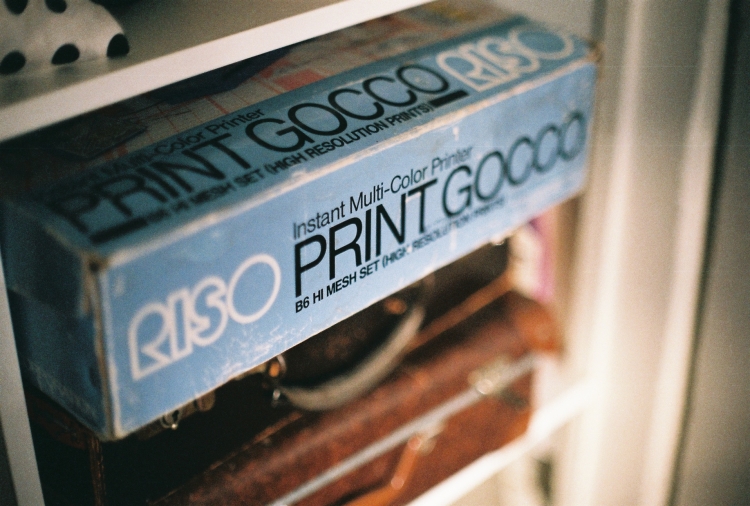

Molly sources a lot of materials from the Internet, and feels extremely lucky to live in a time and place where this resource, and other technologies, are so accessible.

“If you’re doing design or illustration at the moment you’re in the luxurious place of there being a lot of difficult processes, that in previous times would have been a bit time consuming, and a bit expensive, that are now quite quick and cheap,” she says.

”I don’t think it’s ever been so simple before to find sources,” she says. “If I need a picture of a dog playing the piano, you can just Google it and it’s there.”

She has an awareness that these resources do not simply appear out of nowhere, but through a lot of people’s combined archiving efforts. This knowledge has instilled in her a strong sense of personal responsibility.

“I like the idea of contributing to those resources as well,” she says. “Recently I saw some really beautiful drawings in quite an old book, and I thought, oh, I’ll just Google that later’, because I was looking at it at a friend’s house,” she says.

“But then I tried to look for it, and I couldn’t find it,” she says.

She realised then that “it’s just as important to document all of these non-digital sources, and contribute to this huge pool of images on the Internet, as to use the Internet to find things.”

“I like the idea of it being a collaborative thing for everybody in the world,” she says.

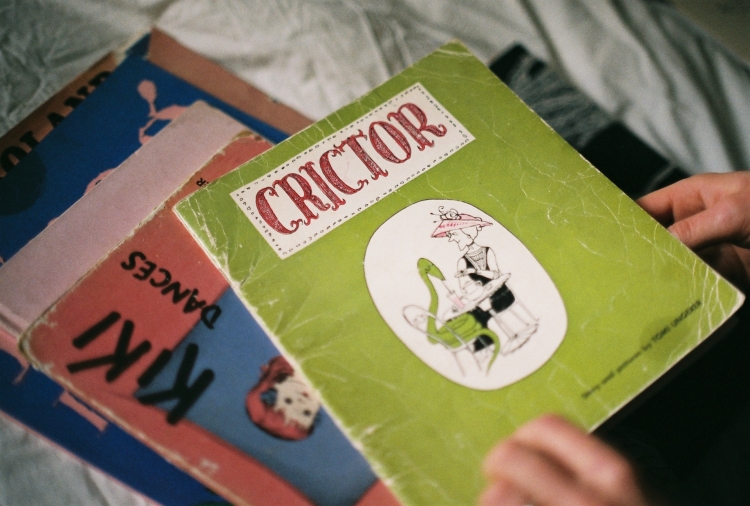

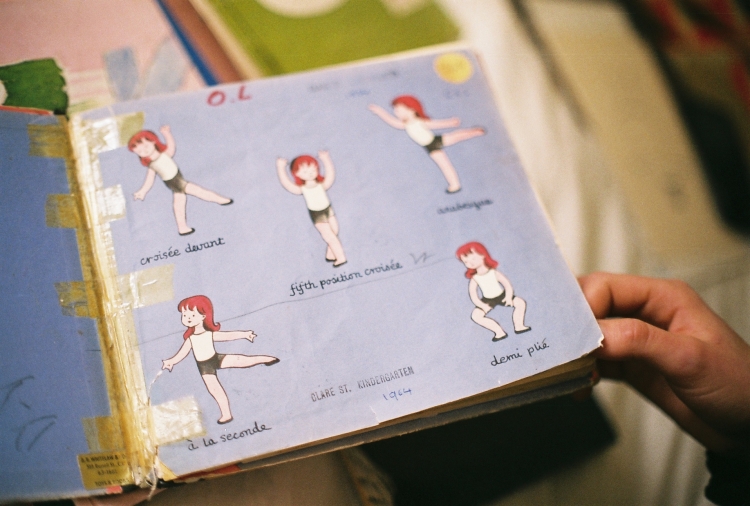

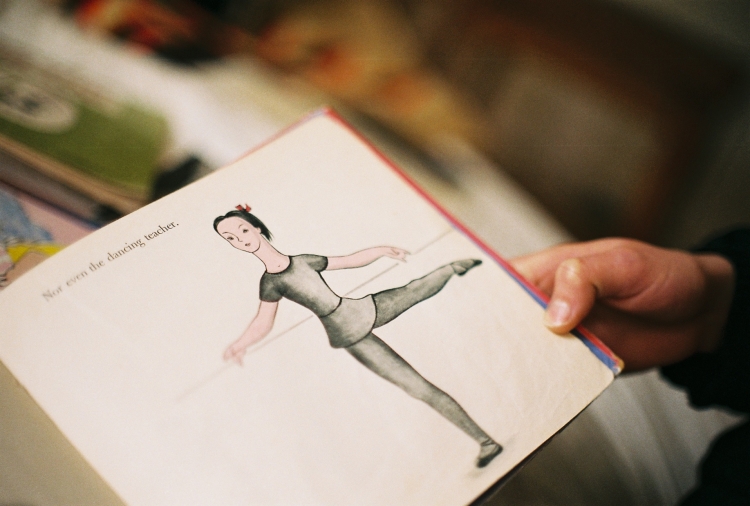

Molly made a blog a few years ago called All By My Shelf. It featured scans of some of her favourite books. One of the books she posted images from, called Kiki Dances, features illustrations of a little girl practising ballet. It received a lot of attention.

She received an email from a couple in America, who had been looking for the book for years. The wife of the couple had had it as a child, and had wanted another copy to show her children. Now when you Google Kiki Dances an image from Molly’s blog is the first thing that pops up.

Whenever she thinks of contributing to this “archival pool of things,” she is reminded of this experience.

A lot of Molly’s visual inspiration comes from children’s books. But her investment in these objects extends beyond that of a mere aesthetic admiration. Molly hopes to one day become a children’s book author and illustrator.

“I remember being really young and in primary school and saying I want to make books when I grow up. Then I forgot about it for a little while, and in the last few years I’ve realised, no, that is what I want to do.”

“When I think about it I get a little tingle,” she says.

The structure of the children’s book appeals to her way of working.

“I like the idea of not having to create just one image, but a series of images which can fit within the same package,” she says.

“The format gives you twenty different opportunities to explain something,” she says.

“The more I discover and the more I see what people are doing now, or what people did a hundred years ago or fifty years ago, it feels equally as interesting,” she says.

Even if she doesn’t find the content of a particular book interesting in and of itself, she still sees something valuable in its existence. “I think it’s the meeting of all these different elements in this one perfect format that makes me feel really excited.”

Until recently she worked as the manager of the Younger Sun bookshop in Yarraville. She way always fascinated to seek out new books to pore over, along with old one’s she hadn’t yet discovered. While everyone she worked with at the store had an interest in the subject, hers was a consuming passion.

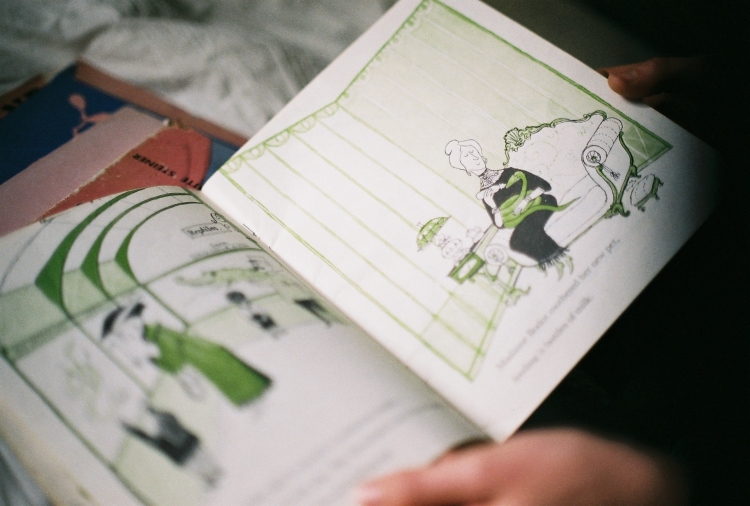

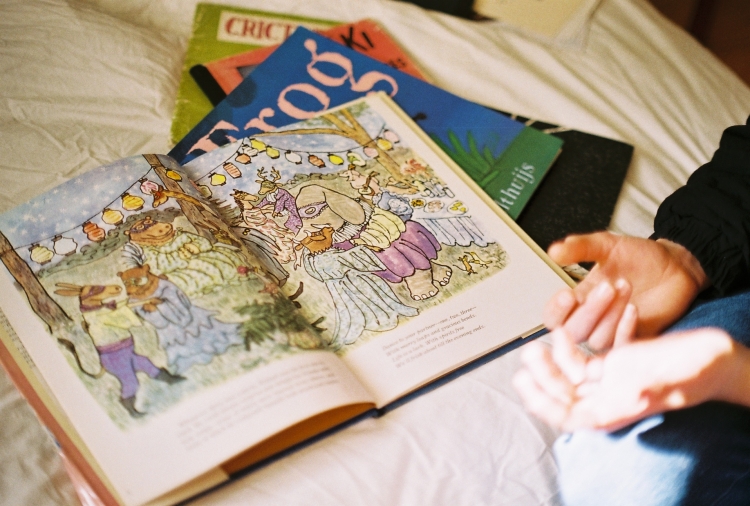

She takes out a stack of some of her favourite books, and lays them systematically across her bedspread. The first is Crictor, the Boa Constrictor by Tommy Ungerer. The author is a compelling to Molly both due to his simple and effective visual style and his transgression as a public figure. “He was banned in America because he was an artist who not only did children’s books but also did these very adult illustrations.”

“I like the idea that his drawings do have this very uncanny humour to them, but they’re still simple,” she says.

Molly favours simple illustrative styles over ‘impressive’ realism.

“I’m never really impressed by things like Graham Base, and he’s a major players in children’s book illustration,” she says. Molly believes that “children’s imaginations can be seeded in the simple as well as in the impressive.”

“I like that can you just use a simple line and put it in a particular way,” she says. “It doesn’t need to be a perfect rendering of something fantastical, that would never happen in reality.”

She likes illustrations that aren’t perfect. She has had Kiki Dances since she was little, as a hand-me-down that her older sister bought in an op shop. ”I loved it so much, because it had these little drawings of this kid doing ballet, and I remember propping it up on the wall and emulating the moves, and using it as this guide.”

“The images aren’t even necessarily anatomically correct, you can tell in this picture the illustrator has gotten to the edge of the page and haven’t quite been able to fit the leg, it’s too short,” she says, “but I think it doesn’t matter.”

“There’s something so related to my childhood about this book, as well. And that’s part of the reason I love it. And now when I go back to it I think what an impression it must have made on me.”

The effect these books have had on her, and the memories they are associated with are often why Molly treasures certain books over others.

When Molly first met her boyfriend, Marijn who is from Holland, in Berlin, they were discussing their favourite children’s books. She was surprised to learn that they had both read a book named Frog In Love, by a German author named Max Velthuijs.

The book had been popular in Holland, as well as Australia. “We had this weird connection of sharing a similar children’s book, two people, from different sides of the world,” she says.

The universal appeal of these books, due to their ease of translation, and emphasis on visual rather than verbal explanations, is another factor that draws Molly to this format as an expressive avenue. “They’re accessible to children. You can give a children’s book to any child in the world and they’ll all get something different out of it,” she says.

This is partially why she is more invested in practising illustration over art.

“A lot of art can be really esoteric and I’m not really interested in making things that only speak to me,” she says. She cites Jeannie Baker’s collage books as a perfect realisation of this universality. Printed without any words at all, “they speak to everybody.”

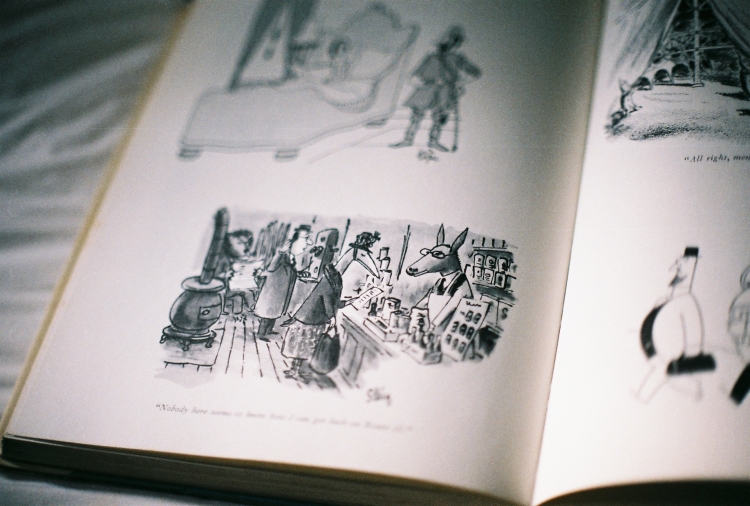

Another illustrator and writer whom Molly admires is William Steig, who was most famous for creating the famous character of Shrek. His drawing style is quite erratic, with sharp, scraggly lines and complex compositions. He is one of the illustrators that she has practised emulating the most.

“An important part of my practice is trying to see how things were made,” she says. “Copying, to get into the head of the illustrator.”

“When you look at his pictures there’s so much going on. He would have made them without Photoshop, or layering,” she says. “They would all be on one beautiful piece of paper, done in black ink and then blocked in, and the setup is elaborate,” she says.

She is also taken with the unmistakability of Steig’s style. “You can see, this is how William Steig draws a pig, and this is how William Steig draws a donkey.”

“It all feeds into one greater idea of storytelling, the same way that Roald Dahl would write a sentence differently to Paul Jennings.”

“I like that idea of having an imprint on something,” she says.

Steig’s drawings also represent the broad appeal of illustration, from children to adults, she so admires. This is typified through his success both as a childrens’s book writer and as an illustrator for the New Yorker.

“I think it’s pervasive and it’s valuable because of that,” she says.

Molly also sees children’s books as having an important social purpose. “I think that children’s illustration is an area that really needs people who are approaching it differently,” she says.

“If everything was Disney, I think that it would be very sad for children everywhere,” she says.

“As someone who’s pretty politically minded, and who’s interested in representing ideas and people and things that are unrepresented generally in all forms of media, focusing on an area like children’s illustration is a pretty socially responsible place to start,” she says. “When I think about my contribution to the world and working within an industry, the thought of working within children’s books feels rewarding.”

Molly is leaving Melbourne this year to live in Berlin once more. She is excited about the prospect of setting up a studio there, and having the opportunity to focus more squarely on her ambition of becoming a children’s writer. She wants to work on developing her writing skills in the same way she has her visual style.

“I find the writing part really difficult because I’m not really a writer,” she says. “I’ve written some things that I’m really excited about, but I’ve realised that with the amount of practice I put into drawing and the visual side of it, I don’t want to just dabble in writing.”

“But I guess once I have the time and I can set myself and think about it deeply, hopefully something can happen and my ideas will feel more solid.”

She is also interested in finding a collaborator to work with, a writer who shares her vision.

“The greatest books have always been the result of some really fantastic partnerships,” she says.

She also, however, acknowledges that there will be “difficulty in finding a likeminded person who would fully understand what I want to do visually as well.”

She is very aware of what makes the good, as well as what constitutes the bad in children’s literature.

Often people would come into her bookstore, and tell her about their great idea for a children’s book. “I’ve realised a lot of people will have ideas, and they will be, say, about a pig, that doesn’t like to share, and he learns how to share.”

This reliance on straightforwardly “didactic,” and simplistically moral plot structures makes for uninteresting story telling.

“I don’t think it’s very exciting for anybody,” she says. “Not for the person reading it, and probably not for the person who wrote it, either.”

She takes issue with authors who are set on “telling children about being brave, or being strong, and doing the right thing.”

“The world isn’t really like that,” she says, “the best writers and illustrators are the ones who ignore that black and whiteness and show that the world can be complicated.”

Roald Dahl, she says, is a perfect example of this. “He’s willing to put people in his books who are despicable, or who have hearts of gold but then have assholes around them, and that even if you do the right thing all the time you might not end up in a particularly amazing place.”

“I think that anything that’s too preachy sucks and that things that show some kind of social realism for kids are really important,” she says.

Molly thinks that children’s books as a genre have a long way to go in terms of cultural and social inclusivity. She is most interested in books that “represent the under-represented,” in a meaningful way.

“It can show something that is quite beautiful and mundane that isn’t necessarily because it’s different, it’s a good story regardless of that,” she says.

“I think there’s massive gaps in writing about those sorts of things, like children with disabilities, or non-traditional families, or children who are from other ethnic backgrounds than being white,” she says.

She is interested in moving away from this “narrow-minded standard of characterisation,” and towards a rubric that challenges the status quo, without being overly “preachy,” or tokenistic. As with her craft, she says “it’s all about finding the balance.”

When we finish talking I take photos of Molly in her bedroom. Somehow Chippy always finds some way of entering into the frame, either tucked under scattered bits of paper, or under her owner’s feet. When I take a final portrait of Molly holding one of her paintings, Chippy insists on being in it, stretching out her long torso to rest her small legs on her owner’s thigh. She looks up with a wide-eyed urgency as Molly smiles downward, meeting her gaze. I wonder how, given the brief, Molly would choose to render her favourite bits of her little muse; her armpits and her lower lip. How she would convey the impression she has made on her, in the manner of a character from one of her well-worn books. How she might draw her to remember her.

You can see more of Molly’s illustration and collage work on her Cargo Collective here, and her children’s book blog, All By My Shelf, here. Her former blog, Good Start, is here.