There is a kind of partnership forged in the teenage years that is unparalleled at any other life-stage. It’s far deeper than the instant child bond; kids are fickle, and mean, and cruel, and all those other nasty, uncomely things. Their friendships melt like so much fairy-floss– in the time it takes to win a race across the monkey bars, or to scoff a gifted segment of Roll-up; before you can even utter the words ‘wet willy’ they can be over.

They’re more real than adult friendships, those lifeless sham-marriages perpetuated through polite Adult brunches, Adult dinners, and Adult drinks which can sometimes, but not often spill into Adult debauchery and unwelcome Adult three-day hangovers.

This kind of undying teenage devotion, existing in the gap between the first rejection of parental attachment and that initial object of girl or boy crush-dom, is characterised by countless hours spent on exasperated parents’ landlines unpacking, blow-by-blow, the minutia of that day’s gossip; trolling the mall together until curfew to see and be seen; gushing to each other on topics as varied as your shared adoration or hatred or indifference for whatever teen idol or band or classmate you so choose at that moment. It’s assumed that only you two will ever get it, too.

You feel empowered in the earnestness of your friendship and it’s at-oddness to everyone and everything else– to all the stupid hegemonies of the big bad world. It’s a demanding mania, where Best Friends Forever rings less as ’til-death and more as a death threat.

It’s odd that such an extreme situation is so commonplace in these years. As we have grown older, though, this intensity of platonic connection is increasingly rare and rarely long-term.

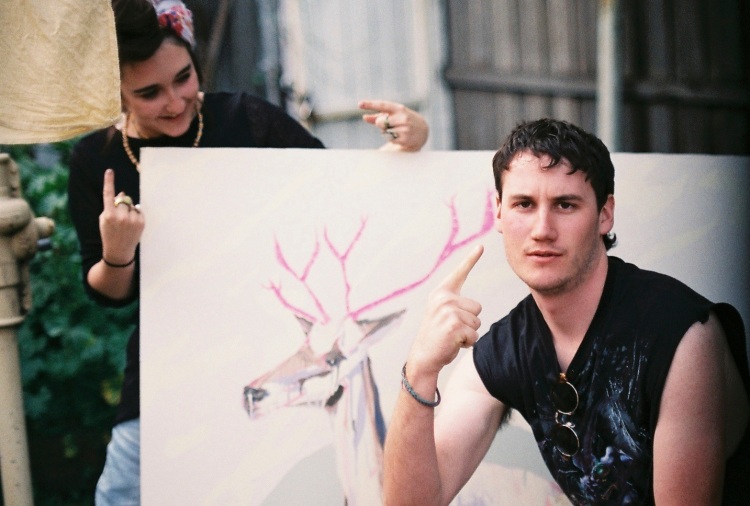

And in Melbourne, a town where the art-world seems to be so strictly demarcated from the live music scene, Nick Brown and Misha’s pal-dom as articulated through Friendships seems even rarer. The music-art collaboration happened organically, accidentally, all of a sudden, as one of these friendships– where the kid you hated the stupid guts of in fifth period became your BFF in sixth and remained so until the final assembly.

When I arrive at Misha’s Footscray home they are sitting in the backyard in the afternoon sun, sinking tall glasses of wine and juice and nursing their collective hangover from a particularly fevered Friendships outing the night before. They are listening to an interview with Prince, on a plastic record carved in the shape of the artist, given to Misha by her uncle. The pair oscillate in bursts between Beavis and Butthead-esque cackling and reverent sighs, in a kind of symbiotic to-and-fro.

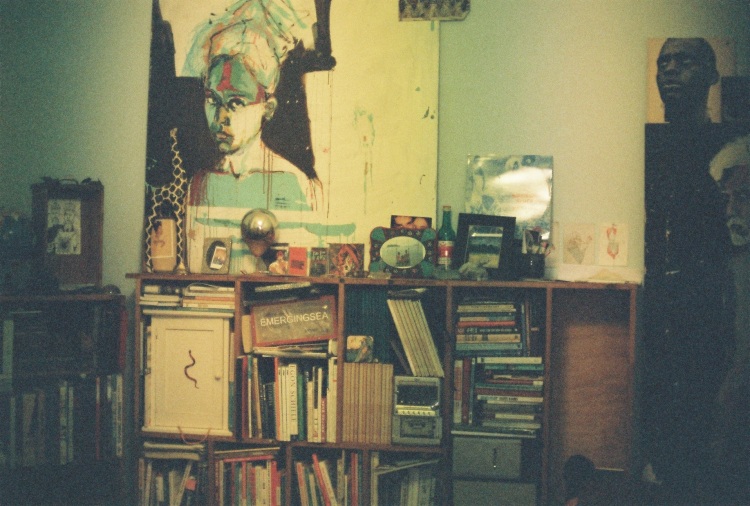

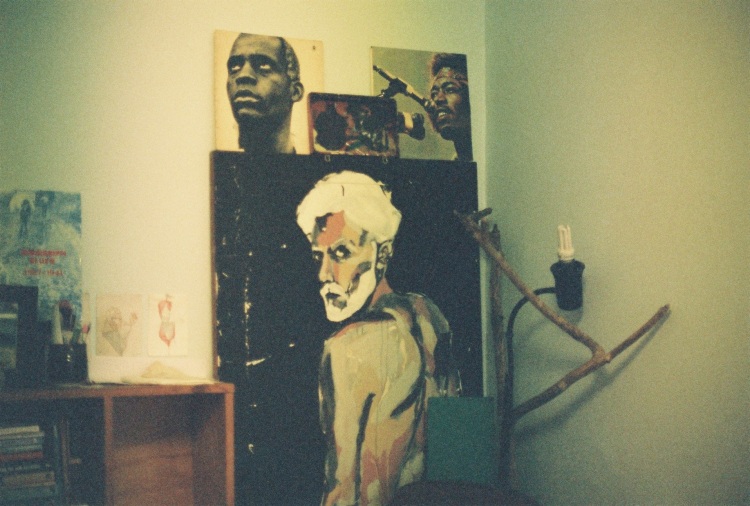

After I down a few wine-and-juices we head inside to do the interview. The place has a humble higgledy-piggledy quality, with books, records, paintings and knick knacks stacked in toppling and sometimes ingenious piles. Some of the neatly stacked cupboards examined more closely reveal themselves to be composed of precariously stacked cardboard boxes. Misha’s paintings dominate the lounge; they are huge, unsettling expressionistic portraits with sinewy bodies and sunken eyes painted in harsh relief. Her art spills into everything, a portrait of her father peers up, peeling slightly, from the home-made table in the backyard. Desiccated VB cans surround his gaunt face, like candles on a shrine.

The project started, as with many contemporary music projects, in a bedroom, where Nick began a music project known briefly as ‘Friendship.’

“I really wanted to be a singer-songwriter, but I can’t sing, so I gave that up pretty quickly,” he says. “I started writing music that I would like to listen to; bass heavy, rhythm stuff.”

Nick’s observations swing between self-deprecation and frank wit. He doesn’t take himself, or anything much else, particularly seriously, preferring to speak in blunt and unpretentious jabs and totemic witticisms. Misha has a similarly irreverent attitude, breaking now and then from her frequently insightful observations into a highly contagious, hysterical cackle.

“Nick came to an exhibition that we were doing,” Misha says. “A friend of a friend brought him along.”

He saw her paintings and was taken by them, and they talked about her doing a cover for one of his releases. They met up in the “heinous place,” she used to live in which was a self-proclaimed “hoarder’s fucking paradise.”

“Then we talked about doing live stuff together,” Misha says. Misha is also an emerging video artist, and they thus decided to integrate a visual live show with Nick’s beats.

“I had a show was coming up, and it was probably one of my first shows, at the Liberty Social,” Nick says.

The idea also sprang out of a shared sense of dissatisfaction with the flat performative format of the beat-maker show.

“When beat-makers perform live it can be a bit mundane in a way,” Misha says.

Nick puts it a shade more delicately; “It can be boring as fuck sometimes; it’s not engaging at all; you might as well be in a corner by yourself in a good listening spot and having a boogie.”

The idea, to create a more immersive audiovisual experience, has evolved through the progressive intermingling of their artistic and musical interests. Nick, the beat-maker of the pair, is fairly flexible with his set. Misha maps complementary visuals along with his music which are also assembled live, and are projected onto whatever screen layout they have available.

“It’s a funny journey where in live shows, Nick is the leader; he’s playing the music, and my job is basically to follow it visually, which I really fucking enjoy,” Misha says. “In a lot of of my personal work in painting and video art I’m really interested in the ideas of intuition and improvisation.”

The shows started out as a simple collaboration, and have grown more complex, and performative over time, with a heavier emphasis on interaction and audience involvement.

Nick’s music has also evolved over time, particularly due to the emphasis on live performance.

“Playing live has changed the music I write, because I want to play tracks that I would want to play live,” he says.

“I think I enjoy playing club nights most,” he says. “But I still write a lot of down-tempo stuff, which hasn’t really seen the light of day.”

“I like to write music, and then I like to write some dumb shit as well, just shit that if I was having a dance party I would like to dance to.”

“I like to write a few bangers,” he says. “I like to exploit how cheesy they can be and to explore that.”

Technically, like a lot of beat-makers, most of the music Nick generates is software-based, and is configured through the manipulation of sound rather than through straight musical experimentation.

“I use Ableton Live,” he says. “And I mostly use data- I’ve mapped my controllers to control that program as much as I can so I don’t need to have the computer anywhere near me, so I can just discard it and use them as a musical instrument even though there’s nothing musical about them.”

“I guess in a sense it’s a bit musical, but mostly it’s just computer nerdery-stuff,” he says. “I’m not really gifted,” he breaks into a self-deprecating chuckle.

“I like to manipulate sounds, and I like to play the keys, and I usually bring my synth to live shows,” he says. “I wouldn’t say that I’m very good at all at playing them but I give it a crack.”

“We try to keep it pretty open, I can improvise to an extent, and Misha is pretty open to improvise, well her set is pretty much improvisation,” he says. “Mine has an electronic framework, and there are guidelines that I stick to.”

While Nick manipulates his sounds live, he generally has a pre-existing format, while the formulation of Misha’s set and the visuals she mixes is entirely improvised.

“I have a little archive of visual samples,” she says. “It’s probably about 80 per cent original stuff; my eyes are always open for little things that might be really cool to film and then to distort and then to project.”

“Then the other 20 per cent is, stuff from YouTube or really amazing documentaries that I’ve pulled,” she says.

“I work with Emidi as well, so I can cross-fade between images,” she says. She demonstrates the software, where the controls make it easy to glide between her archived video footage. She inter-splices a clip of a friend dancing in a hypnotic rhythm over a background of computerized imagery of green spiraling light, before transforming slowly into a video of a spider.

“Misha has a data controller as well, where she can map all the variable that she needs to map, and then she can fuck with it,” Nick adds.

Their set is usually completely unrehearsed and as such has evolved through their growing awareness of one another’s patterns and rhythms on stage.

“I might say, I’ve got this new track,” Nicks says. “And then Misha might ask me when I’m playing that track, and I’ll say, I don’t know- I’ll give you a nod.”

“And you never do,” she laughs.

“When we first started to play we used to play facing each other and I think we really liked that for a long time, and then due to the logistics of some places that we played, we needed to be side to side, and I think that opened up a whole new level of communication,” Misha says. “I think there’s a lot of immaterial interaction, where it’s not explicit.”

“We don’t chat but I know what Misha is doing,” Nick says. “Some of the time when I’ve done live gigs without Mish it’s kind of sucked; her onstage energy- if she’s not there I get a bit down.” Misha agrees.

“When I’m doing the visuals, I stare at Nick quite a bit, because I’ve gotten to know his body language while he’s playing and his hands movements especially, and when there’s a big drop about to come, I can get my stuff ready,” she says.

“I think it’s funny as well when I fuck up and they don’t match,” Nick interjects.

“I think it’s really great,” she nods, “I’m all for seeing these funny mistakes that artists have made, whether if it’s with live music or at an art show, or a painting, I think that is really something that’s valid.”

“Especially when it’s electronic, where it’s seemingly a press-play and go game; it brings a bit more of an original element,” Nick says.

“I think that’s part of the reason that we do integrate the improvisation aspect into the shows,” Misha says.

This shared reliance on and appreciation of the improvisational format and its potential mistakes and mishaps is aided by their similar attitudes to their work. “We aren’t the type of artists that have a lot of snootiness about us,” Misha says.

“We’re not precious about our shit,” Nick pipes in.

“Which is something I used to be personally, I used to be so precious about my work when I started university, I was exactly the word precious; I used to hold all my concepts to myself and I would never talk about it,” Misha says. “Then I met Nick who has a very relaxed attitude to his work.”

Nick and Misha have both respectively studied their creative pursuits at university, with Misha completing a degree in Fine Art, majoring in painting, and Nick studying Sound Engineering, but their skills and their outlook has developed significantly through the formation of their partnership.

“I sort of took that on since working with (Nick) and I think my work has definitely flourished because of that,” Misha says. “You don’t want to be serious all the time.”

“It’s tiring and it’s painful sometimes,” Nick elaborates. “If you’re trying to do the most intelligent shit all the time you kind of suck the fun out of it.”

Friendships navigates the interstitial space between the art and music scenes in Melboune, and as such they are used to adapting their sets and visual aesthetic to a wide variety of venues.

“Sometimes we play at five on a Sunday and do a chilled set,” Nick says.

“Not a lot of pre-thinking goes into it, but I think definitely when you’re in the space and performing the vibe of the whole space and its energy impacts,” Misha says.

“When we get to a space we can kind of vibe on it,” Nick says. “If it’s a kind of gig night where you expect people to be vibing and no one’s vibing.”

At a recent gig in Brisbane, they became extremely frenzied from the energy they were receiving from the crowd.

“We nearly did our necks out,” Misha says, giggling. “We were dancing so hard,” Nick adds.

“We were going crazy on stage because it was packed, and we could see that crew that we travel with a lot with were at the front getting really into it, so me and Nick in turn fed off that energy,” Misha says. “On the plane the next day we were turning with stiff necks, we were so sore, my neck’s still cracking from it,” she says.

“We’ve done experiments as well, with the Brunswick street show,” Misha says. “That was something a bit different that we did.”

The show, at Brunswick Street Art Gallery, was a collaboration between Misha and Nick in a different format to a conventional Friendships gig. It featured a series of paintings by Misha, propped around the space. They were completed in her signature figurative, though experimental style of portraiture, with sharp, sculptural bodily forms, heightened contrast and muted colours. It featured a sound installation calibrated by Nick.

“I guess that Friendships’ live shows are music first, and then visuals following, and then we did this show at Brunswick where it flipped a bit, where the visuals came first,” Misha says.

“While I was painting, Nick would come into the studio and record studio ambience,” she says.

“The paintings were two portraits of people looking back over their shoulder, because at that time I was trying to paint depictions of people looking at paintings,” she says. “I got really obsessed with this moment where you’re looking at something and someone calls out your name; that moment where your attention shifts.”

The sound was a result of a juxtaposition of live and recorded sound, overlaid so as to sound ambiguous.

“Instead of it being anything musical it was microphones in the space to capture what was going on in the gallery space,” Nick says. “There were live microphones running and you could put headphones on that came out of the paintings and so there were sounds of Misha painting, and then there were sounds of the gallery space, so a lot of the time people didn’t know what the fuck was going on; it was both associative and dissociative.”

“It got a bit schizophrenic times,” Misha says. “The painting were on the middle and then the microphones were on the edges of the gallery, so people would just be unknowingly standing next to the microphone and having a conversation, and someone would be in the middle listening to the headphones, and then would hear these people talking that were on the other side of the gallery, but it was quite distorted as well. “

“It had these self-automating effects, with weirdish delays,” Nick explains. “Some of the time it took little granules of the sound and sort of exploded them, so it would take that tiny little fragment and blow it into a big granulate cloud.”

“When people figured it out they’d go to a microphone, and say ‘dicks and fannies, butts!’” Misha laughs. “I had this funny moment where I was at the show where I was talking to this woman and she was getting really into the work and had these philosophical ideas of what it was about.”

“She had a son who looked about eight or so,” she continues. “He had the headphones on and I could see he was trying to figure out he was laughing and having a really good time, in that moment, it was a cool moment of the work being enjoyed on a few different levels.”

“And that’s a trait that carries through, a lot of, even our bass heavy shows, club shows– they’re always relatively accessible,” Nick says.

While the live show is the central point for collaboration between the two, there has been others. Misha recently created a clip for Nick’s track, SSLLOWW. The song features an a cappella, tonally-dropped rendition of Kylie Minogue’s ‘Slow,’ set to haunting, repetitive beats and electronic harmonies to which Misha created visuals of a girl dancing hypnotically in front of a projection of swirling green light, with overlaid animation. The song was the result of an unexpected and humorous collaboration between the two.

“One night, I was just at home, with me and a few other people, and we just kept on singing that Kylie Minogue song Slow.” she says. “We just kept singing that song in dumb voices and making dumb Photobooth movies, with tulle on and shit, just really drunk and high, and then I was like, we’ve gotta make a video to the lyrics of that song.”

“I think it was the next day and I was like fuck I want to make a track, so I started writing this track, with that stupid a cappella in there,” he says.”

“It was so funny because of the way it came about,” she says.

Both of the artists seem to have found something acutely inspiring in the other, in the least pretentious sense possible.

“I will go through lulls— I was in a lull for a few months, I couldn’t write anything— I think now that Mish has started painting again, that I can write music again,” Nick says. “I get inspired by a lot of things that I hear, but a lot of the time I’m thinking, will Mish like this stuff? I don’t want to play stuff that will sound really stupid and she’ll be up there embarrassed; so that’s a bit of a factor.”

“Most of the time it’s shit that I like, essentially, and then things that I’d like Mish to like,” he says.

“We have a funny vibe in that way,” Misha says. “Being a visual artist, I’m so inspired by the way music is made and released in this electronic beat scene that we’re sort of involved in.”

“I feel like it’s a lot more of a friendly environment than the visual arts scene in a way; there’s these bedroom artists who are like, I’ve made this, I’ve put my heart into it, and I’m going to put it on the internet and anyone can download it for free,” she stresses.

“In comparison to the visual art world, which is this scene where you make some work, and then you have to write a proposal, and then you have to hope that a gallery picks it up, and then you have to pay hundreds to dollars, and then if you sell something you have to give the gallery that commission,” she says. “It’s kind of funny.”

Nick, as a musician, was bemused by the whole art scene financial dynamic. “I didn’t understand that when we did the Brunswick show,” he says. “I thought, you’re putting art into this space, surely they should be paying you for that.”

“Even if you compare an art gallery opening to a gig, the differences are enormous; at an art opening there’s a lot of judgement in the air, there’s this kind of weird pressure to be this interesting artist, and I’ve found with the experiences I’ve had in the music scene, it’s so much more fun,” Misha says.

“The art scene has this really competitive nature, and it’s a lot colder, and the music scene is a lot warmer,” Misha says.

She’s not simply accepting the way things are though.

“I’m looking at releasing art in the same way that music is released— I’m working on releasing things through the internet— I’m talking about making these works, and using the internet to promote it, and giving things away for free, which is, I think can be really beautiful,” she says. “There’s definitely a difference between the audio or sonic way of making work, and I just really love the sonic way.”

“It’s really good in Melbourne as well, everyone is really friendly and open, it seems like the community we have is so nice and supportive of each other, which is sick,” Nick says. “I think, why not totally boycott the galleries and do an installation in a live venue?“

“The music scene in Melbourne is really quite inspiring and encouraging as well,” she says, “not that I think the gallery is dead or bad or anything but-”

“I think they need to check their shit, honestly,” Nicki interjects. “I was bewildered, I just didn’t get it, and I still don’t get it, and that’s why they need to check their shit,” he breaks into a chuckle.

“Most of the music I listen to apart from Prince, is Melbourne stuff, which is great,” Misha says. “I get inspired by it visually, a lot of inspiration is music and not visuals anymore, it’s a bizarre thing.”

“When I was an angsty little dumb teenager, I used to draw in my bedroom at night when I was angry at mum; I’d listen to this music, and make a drawing to that snippet of lyrics,” she says. “And then that didn’t happen for years, and then it’s funny how I’ve come back to it with Friendships.”

When I ask them where they expect to go with Friendships they seem equal parts excited, ambitious, and characteristically humble.

“In a egotistical sense, I always have this idea that I want to write this new form of music, I’d like to be a fore-runner of something new, and that’s kind of a pushing element, because a lot of the time I want to bring a sense of nostalgia, but also go into an area that I’ve never heard,” Nick says.

However, he admits that, “I didn’t see it going very far at all from the start, so it’s like every day is a little grace, because it’s always just been a hobby, it’s come from the bedroom.”

“I had a goal of just playing with one of my favourite artists, supporting one of my favourite artists, and then we supported Shigeto, and that was fucking amazing even though I played a stinker of a set,” he admits.

“It’s always just a hobby and a passion,” he laughs and adds in an affected accent, “I’m a passionate artist.”

“At the same time, I’ve got a shitty job, and that’s paying the bills, not music,” Nick says.

“I have these fantasies of this ridiculous stage that’s just a sculpture that we can stand in with projections,” Misha says. “I’ve been wanting to have a real installation as a show, rather than just pulling a screen down and projecting onto it.”

“I’ve been making these big cubes out of it and hanging them in front of the projection screen; I guess when you get different textures it becomes a bit more interesting,” she says. “I project onto the tulle, and then each surface captures the projection and warps it a little bit, but it still projects right through it, so you’ve got the untouched visuals, but then you also have these warped ones in front of them.”

“I did actually name it Purple as well, I named my tulle, I’m really attached to it,” she breaks into her ever endearing cackle.

“It’s difficult, in bars around Melbourne, which is where a gallery could be different, in a gallery you could have two weeks and build this incredible thing.”

“But they don’t have sound systems, either,” Nick adds.

“It’s funny; we’re in this in-between ground where we don’t really have the logistics and tools and money to do these elaborate grand things,” Misha says. “It’s kind of making do, doing what we can.”

“We gig fairly regularly, and they just sort of pop up and I haven’t done much, to be fair, usually we just go in there and wing it, but we do have these grand ideas– we want to have interactive shows,” Nick says.

“I think the more we try to persevere with it and the more we keep on trying to make things happen, to come to fruition, they will eventually, even if it’s just once,” Misha says. “I’d happily have this as my day-job, but that’s probably not going to happen.”

They will be more than happy for the project, forged from its humble beginnings in a hoarder’s paradise somewhere in Melbourne, just to continue, in some form; to survive in the little niche they have carved out for themselves.

2 thoughts on “Nicholas Brown and Misha Grace”