Generational share-houses inspire in me the same kind of banal mysticism as a well-worn hand-me-down. It’s a similarly mundane response to that apolitical Sisterhood to those eponymous travelling pants.

Mundane histories of long-forgotten drama and desiccated gossip ingrain themselves into the very walls of these places, along with the greasy blue-tack stains. Tales of erratic housekeeping and absent-minded neglect emerge in the Pollock-like drips that zig-zag across the ever-morphing shade of carpet. They evoke the questionably concocted cocktails of esoterically themed house parties past. Traces of old house-mates soak into everything; a slowly collapsing couch set here, a fossilised instant noodle stash there. There is something about this carefree (or careless) passage of quasi-adult life that stains every nook and cranny of the houses it touches, borrows, and steals from faceless landlords. Like a particularly stubborn, mooching poltergeist.

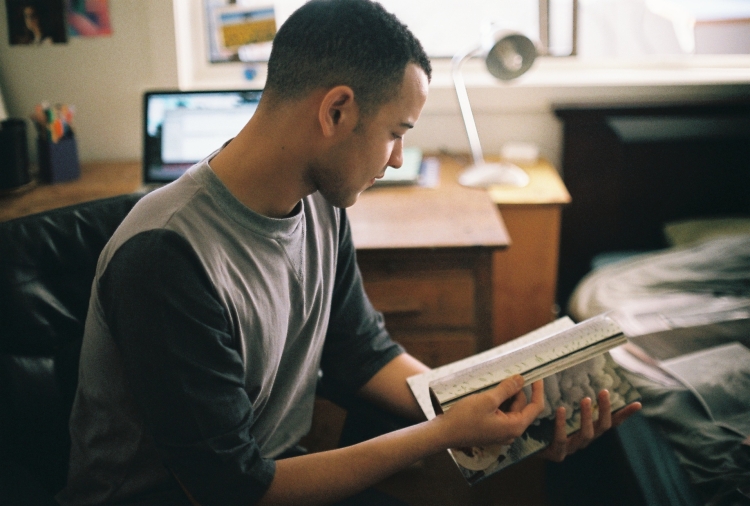

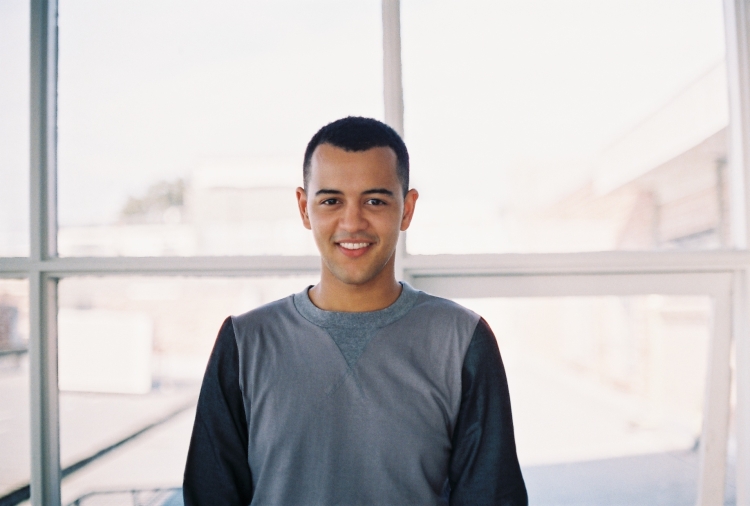

Editor and writer Tsari Paxton’s place is site to one of these slowly unravelling sagas. Situated in a particularly sought-after patch of Fitzroy, the, top story apartment is almost too generously appointed and well-placed for a long-standing share-house. Large French windows surround its perimeter, spilling sunlight generously wherever they preside. Tsari gives me the tour, and we end up in the largest communal space; the sun-room. Its large white windows look onto the rooftop outside and hints at the leafy park below. This interior space used to be a balcony, he says, but was turned into a sun-room in a hasty renovation. Consequently, the French windows of his bedroom look onto the interior space instead of to outside. The room is already balmy in the early Spring sun.

It’s a really nice space, he tells me, but it gets too hot in summer, because you can’t open the windows. I ask why.

As always, with Tsari, there is a story to be told. When he divulges one of these collected articles of fodder or personal anecdote his eyes gleam and his bright voice bounces along with a rare combination of conspiratorial glee and empathy.

The apartment, he says had been a share-house for a long time, and hence the site of countless parties. In summer these affairs often culminated in guests liberating themselves through the sun-room windows from the claustrophobic indoors out onto the rooftop. At one particularly raucous party a few years ago, a girl had fallen through a skylight and been gruesomely impaled on a piece of gym equipment below.

It’s one of those stories that becomes instant folklore, the kind of rumour that is compulsively consumed and repeated, again and again. Tsari had assumed it was an urban legend until one of the attendees of the ill-fated soiree had visited the house and confirmed it to him. It’s probably a tale that has been regaled ever since. A “but-for-the-grace-of-whoever” fable about the mortality of the party-going twenty something.

Stories like these, as real-life realisations of the countless what-ifs that plague young people, fascinate Tsari. And since he was young, Tsari has always enjoyed detailing these stories of the people around him through words.

“In Primary school I made this gossip magazine, cutting out people’s photos from the school photo and putting things like ‘Louisa and Morgan open-mouth kissed,’” he says. “It was like NW with people I knew.” His next memorable self-publishing experience was a similar exercise.

“When I was about 15 I wrote a 100,000 word Survivor fan fiction story, featuring people I knew.” While he has always been interested in writing, he has always been equally interested in printing his words.

“That always a big thing for me, having the physical version of it,” he says. “The way words look on paper excites me.”

Tsari completed his Bachelor of Arts at the University of Melbourne a few years ago and as with most people in his situation, “I felt obviously lost, like lots of people do, and I went overseas when I was about 21, and I was kind of stressed out thinking, what am I going to do?”

He thought about what he enjoyed the most, and was best at, and kept coming back to the idea of writing, and of communicating this writing through print. He completed a Masters in Communications at RMIT, and decided to channel his skills professionally into the more practical avenues of communications, marketing and public relations. A realistic appropriation in the face of an ever-shrinking publishing industry.

“That’s what I was doing educationally, but then the side project with the zine fulfills what I would really like to do,” he says.

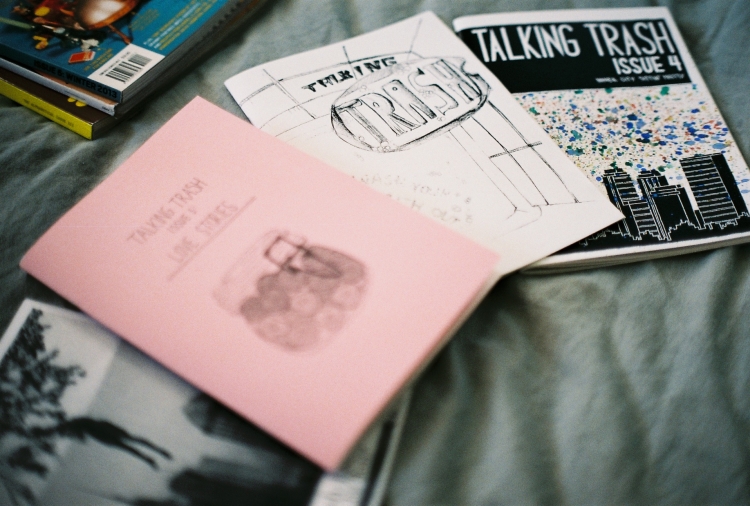

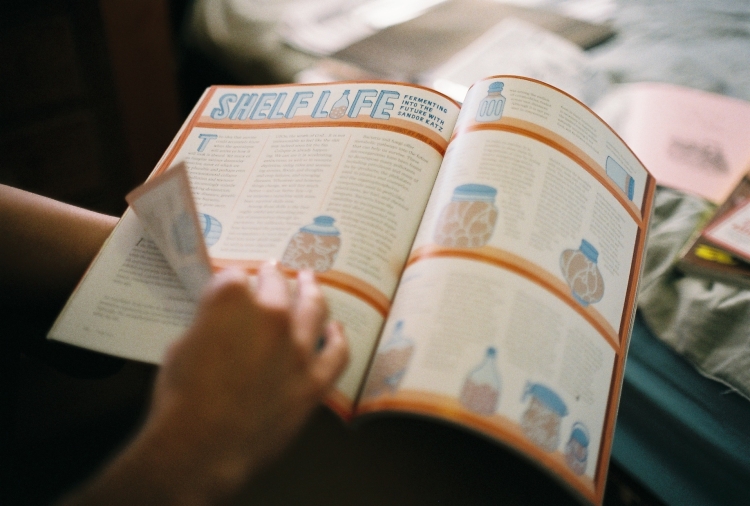

Talking Trash is editor Tsari’s passion project. The zine was first published in 2012 and has had four issues thus far. The idea first began to emerge when Tsari was living in Berlin, and had a lot of time to reflect.

“I’ve always really enjoyed buying magazines and reading them,’” he says. “I was thinking about what magazine I would really like to work for, and then I realized that there weren’t really any that really excited me.”

While he enjoyed reading specific interest magazines, about fashion, tennis and gay culture, he wasn’t attracted to creating this kind of extremely specific and thus potentially alienating content. He wanted to work at something more universal; something that would appeal to a wider audience, with varied interests, backgrounds, and from different social groups. He wanted, particularly, to create a magazine for young people, about the broader experience of being young.

When he got back to Melbourne, he was talking with some of his friends who he had studied with, including Paige Farrell, who is now sub-editor of the zine. “I said, I want to make something that’s not about culture, and not about art, because that’s what most magazines for young people are about, some specific interest.”

“At the end of the day it ends up being about an art gallery you’re never going to visit, or clothes that you’re never going to be able to afford, or music that you’re not that interested in,” he says. “I wanted to make something that’s just about experiences and opinions and people’s lives.”

He was more interested in the idea of creating a publication that dealt with the day to day experience of being young and the issues that arise through this lived experience; stripping away the pretensions, cutesiness or lofty posturing which a lot of youth magazines he knew of fell into.

“I think I just find people’s stories really interesting, and that’s what I want to read about and what I like to write about as well,” he says. “I like articles that are about something specific that broadens out to be relatable to lots of people,” he says.

Some topics that have been covered in the magazine include young people’s forays into sex work, and the Peel , Collingwood gay nightclub’s sexist door policy. These stories relate to broader concerns that affect young people as a whole, raising questions about the way in which we treat and value our bodies, or the issues of gender discrimination within and around young gay subcultures.

Through the zine he can live out his dream of being an editor, but on his terms, without the huge industry pressures of working in publishing.

“When I started my Masters, I learnt about the publishing industry, and what it’s necessarily become,” he says. “I don’t really want to be an editor for a magazine, because you end up just talking to advertisers, so in order to get published you need to run a certain number of ads, so your role as the editor at the moment in commercial magazines is basically to be running ads in the magazine.”

“That’s not really a fun job at all,” he says.

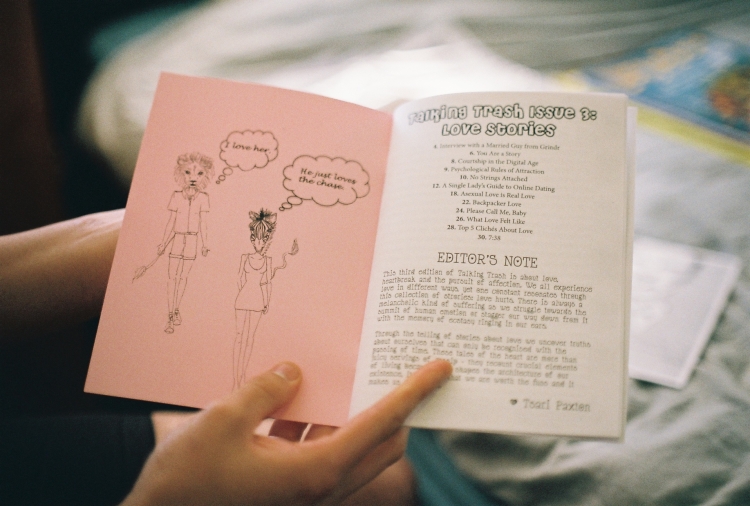

Each edition of Talking Trash has a different theme which is decided by Tsari, through discussions with his two sub-editors, Chris Di Pasquale and Paige Farrell.

Generally he chooses the theme around a topic he is currently himself interested in writing about, and that has “potential,” for a wide range of exploration.

“The first one was Get Yourself Out of the Gutter, which as a bit bumbling as a theme, which was just about the crazy things young people do to get money, like crazy drugs, and prostitution,” he says.

“Then the second theme was Who’s the Boss, which was about dominant institutions in the society, like Government, education, religion and young people’s relationships to them,” he says. “The third one was about love, and love stories and the fourth one was about the city, the site where all the fun stuff in life happens.”

The process of gathering content has evolved with each edition and as the readership of the zine has expanded. “The first one was just me and a couple of other people, the second one spread to a bit wider of a net of people I knew,” he says.

“For the third and the fourth one I started to get contributions from people I don’t know,”he says. “For the fourth one we actually sent a little thing out to people in different University courses.” “It’s definitely good to be able to cast a wider net, but of course you get a lot of crap,” he says. “But you get some cool stuff, a couple of girls from Brisbane wrote a really fun article for the fourth issue.”

“In that issue we also ran an article by a guy named Josh Barnes – this short story about a dystopian Melbourne where the rubbish men stop collecting rubbish with a apocalyptic feel – and I really liked it so we decided to have him do one of the readings at the launch party,” he says. “At the launch he came up and introduced himself to me and I asked him how heard about Talking Trash, was it through one of the Uni send outs we did, and he said no, through a friend,” he says.

“And I asked him what course he studied, and he told me he was studying year 11, and to my surprise he was only 16.”

“It made me super happy because I want Talking Trash to include a very wide scope of youth, and be more about a stage of life than a date of birth – that stage of life being not quite settled into your career, you know, still working things out,” he says.

“I thought it was so cool that a 16 year old’s writing could sit alongside people in their late 20s and 30s; and collectively it becomes a kind of time capsule of what it’s like to be young today,” he says. “It’s nice that it spread, and it’s hard to tell, but I think it’s being read by a few people around here and there,” he says.

Tsari and his team also stock the zine at various bookstores and zine shops around Melbourne, including The Sticky Institute, Polyester Books and Hares and Hyenas.

However, he believes that the launch in the best way to get it out to people and to raise awareness about the project.

“I usually get a good turn-out, and when people come to the launch they’ll buy one and then they’ll have it in their house and people will see it.”

When he is selecting content he is most interested in finding work that contains a fresh perspective, or an innovative approach to a familiar issue. Material that he considers publishable is generally “something that I don’t feel I’ve read before, where it’s a point of view or a story where I don’t know where it’s going or it kind of surprises me in some way.”

He also is looking for work “that’s not too cute,” he says. “I find a lot of writing in Frankie with Smith Journal goes for this over-kitsch cutesy vibe, that I’m not really that into; I’m more interested in things that are a little bit more shocking or a little bit more scandalous.”

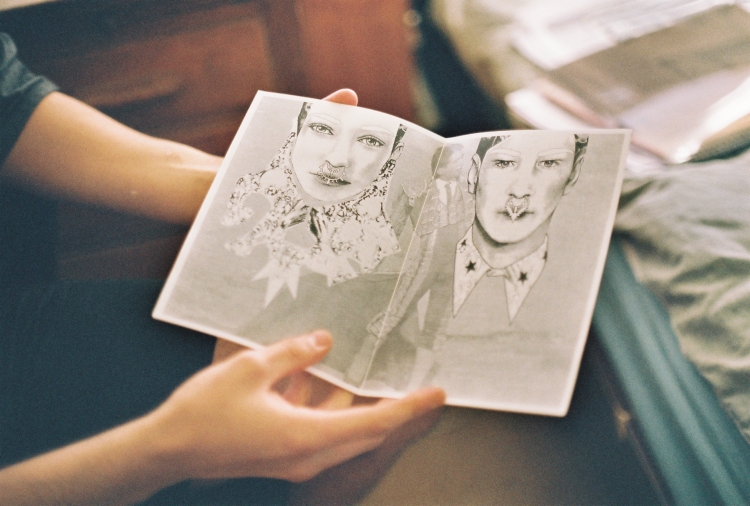

The aesthetic and layout of the zine has has evolved with each issue. “The first one was really lo-fi, with printing out pages and cutting and pasting them, “ he says. “The second one I used InDesign to create, and then everything was a bit more lined up and looked a little bit more neat.”

“And then the third one I think I went too far with that, where things were a bit too boxy and I tried to make it look too polished,” he says. “And I realized that wasn’t right, because zines come from this fanzine culture; it’s about being rough, and cut-and-pasted, and handmade, and that’s what I tried to celebrate in the most recent issue, where I’m hand-painting the covers and cutting out and pasting objects within it,” he says.

The covers of Issue 4 are hand-flecked with vibrant paint, each copy hiding a highly individual paint-job. “I think it makes it feel like a more inviting read, because it makes it more immediate,” he says.

“I don’t want to lose that because that’s the appeal of it, it’s not a polished glossy magazine, it’s a photocopied, handmade, good little read.“

Tsari is, as of yet, not sure where the zine is heading, as thus far his creation of it has been a bit of a roller-coaster, which he takes one issue at a time. “I think when you’re creating something that’s your own little project and it takes so much time to do it’s quite up and down,” he says.

“It feels quite exciting when you make it and you have the launch and people are reading and talking about it for a while, but then, actually at the end of the night, I have a feeling of let-down, where I think; what did I do this for, it’s all over now?”

“And then in a few days’ time I feel good about it again and I think about starting another one.” After finishing Issue 4 he felt like it might be the last one.

However, then he was approached by the Sticky Institute, who wrote and asked that they have a launch party as part of next year’s zine festival. “it was really nice to get a little bit of recognition for your own weird little project, and it encourages you, so I want to make at least another one.”

He is unsure about the future of Talking Trash after the next issue, but thinks it will continue in some form or another. “I think we have a nice website that could continue as a blog, and I would like to continue it on in some capacity, even if it’s just as that,” he says. “Time will tell I guess.”

One of the reasons Tsari has been considering folding the zine is so he can focus more on his own writing practice. “When I have free time I focus on Talking Trash, and I would like to do some of my own writing.”

Tsari’s own work is primarily non-fiction, where he writes about his own experiences. “I think I’m always most interested in writing about experiences,” he says. “By going inwards I think you can examine things within yourself that help you work out how you feel about things,” he says.

“If there’s something I don’t understand, or if it confuses me or challenges me, if I write about it I think I get to the bottom of why,” he says. “I think by inviting other people to read it, it might help other people,” he says. “I like the idea of helping people work out the things in their life that they don’t even notice.”

“I think I’m quite emotionally intelligent and I think I understand other people quite well and I like to write about that and I am forever fascinated by other people and how everyone can be so different, it inspires me to write,” he says.

Like many writers, Tsari gets a lot of ideas when he is busy, and few when he is not. “I have a habit of having a sticky-note with a huge list of dot points of things that I want to write about and, so I save them for when I have time,” he says.

His writing process generally starts with taking one idea or perspective and writing on it until he feels he can’t any more. If he gets stuck after a paragraph or two, he says, the idea probably wasn’t a good one to begin with.

When he has something he feels has potential, he will “then have to go away and come back to it, and see what I actually have; is this something that is worth spending more time on?”

He is not precious with the things he writes, and is generally happy to let go of his work when he feels it has effectively conveys what it needs to. “I’m not a perfectionist- every sentence has to be tight, but I’m not one to go other things a thousand times,” he says. “I don’t see myself crazily obsessing over every last word I kind of am more focused on form and flow.”

One aspect he believes is especially important to good writing, particularly in the personal non-fiction he enjoys writing and reading, is the careful construction and elaboration of the identity of the narrator.

“The mistake lots of people make is that they use I, because to them I has so much meaning,” he says. “I think to really part of the story one of the most important things is you need to make a character of yourself, and explain some of your eccentricities,” he says.

“A good piece of writing also sheds a unique light on something which everyone experiences on some level,” he says.

When it comes to his life experience, there is little subject matter he wouldn’t write about, as long as he was proud of the writing, and he feels it is useful for others to read. “There are some family things that I wouldn’t necessarily want to write about,” he says.

“Actually there was one that I was thinking of writing about for the next Talking Trash, because the theme is going to be something about growing up.”

“There’s always a question with these things, you want to know that it’s worthwhile,” he says. If you’re going to put yourself out there, you’re going to divulge potentially embarrassing or even professionally damaging information, that it’s going to be for a piece of writing that you’re really proud about.”

While Tsari doesn’t consider that he will ever be able to work full-time in the publishing industry, he wants to continue to write for the rest of his life.

Some personal goals include writing for some of the publications that he admires.

“Vanity Fair is one of my favourites, I like the way that it’s long form journalism, because that barely exists anywhere at all,” he says.

“I really like Colours, it’s an Italian magazine,” he says. “Colours is one of the magazines I would most like to work for, and it’s kind about people’s lives and the way in which they happen to be living.”

“Also, Hello Mister, about men who date men, not gay men,” he says. “I really like Thought Catalog, that blog, it’s like a less trashy Buzzfeed; that’s an ambition of mine, I really want to get published on there.”

“It’s rough when your number one interest is writing to foresee what your life is going to be like,” he says. His usually bright tone turns dark for a second. “If this was 1997 I would want to be an editor and I would want to work in publishing because things seemed really fun then,” he says.”I’d probably have a job if this was 1995.”

He is keen for the big change that which revolutionise the publishing industry and bridge the lag behind digital. But he is not holding his breath.

Like other other print lovers, he is making do, applying his skill-set to find a secure niche outside this field. But he and others like him are still obsessed with telling their stories, and those of others; with passing these carefully selected tales on again and again. Starting a rumour of worthwhile things to come.

Talking Trash is stocked at Sticky Institute, Polyester Books and Hares and Hyenas. Issue 5 will be launched as part of Sticky’s 2014 Zine Festival. You can read more about Talking Trash here, and from their Facebook page.