I was a drama kid in high school. Not to the overbearing extent of the Anne Hathaways of this world, but I was pretty invested, nonetheless. And while I didn’t think about it so much at the time (partly because I went to a girls school) I predominantly performed in male drag.

I remember playing lead Viking in the Abba-scored production, Sweden: The Musical. I was adorned with a plastic Viking helmet, swathed in the manliest of hessian sacks, and had a caked-on beard made up of stage makeup as putrid as a ring of old bathtub scum. I took a special relish in contorting my face into a craggy sneer and bellowing my lines in the deepest baritone I could muster—feeling myself to be the ultimate specimen of faux-sculinity.

But I think there was something that pulled me toward drag more than mere necessity. While I was and am perfectly happy with playing girly most of the time, there was definitely something appealing to me in the fleeting transgression offered through the medium.

And inducting new people into drag is one part of Melbourne performer, actor and event-organiser, Olympia Bukkakis’ passion for it.

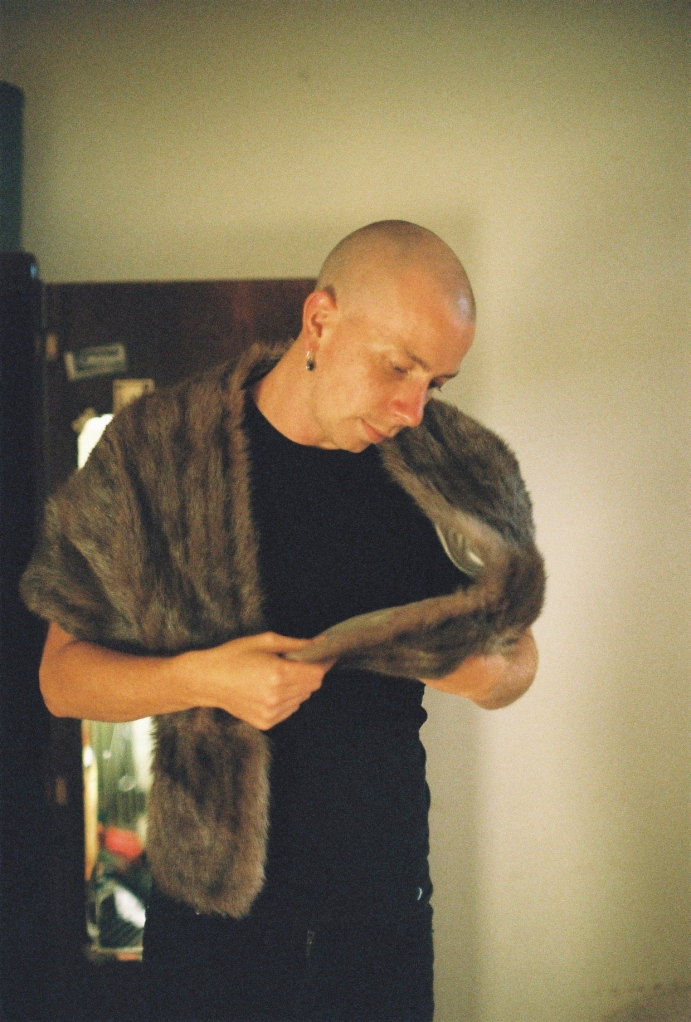

When I meet her at her home, nestled in a quiet suburban corner of the city’s north, Olympia is Taylor. Taylor is a softly spoken and meditative sort—dressed simply in theatre blacks, with a smooth, shaved head, freckled cheeks and a boyish grin, he brews us tea, and we sit by the overgrown garden.

When Taylor performs in drag however, she is far from retiring. She becomes an extreme, dramatic and frequently vile queen known Olympia Bukkakis (a play on the actor’s name, Olympia Dukakis—like most drag queens, Taylor is not immune to a good pun). Olympia appears at various queer nights around Melbourne both as a host, and as an individual performer, and has also acted in several productions with the queer production company, Sisters Grimm. She also co-founded the drag night, Pandora’s Box, with fellow drag performer, Godzilla.

The party started illegally, in an art gallery space, and grew from there. Its most recent incarnation was as a party at the now defunct Gasometer Hotel in Melbourne’s north. The two are currently scouting locations to use to hold the night in future.

Pandora’s Box served as platform to realise Godzilla and Olympia’s shared vision for drag in the north of Melbourne. “Because we didn’t have mentors and we didn’t have a culture, we were trying to start a culture.” They aspired towards creating a co-operative and nurturing expressive space.

They took partial inspiration from the iconic drag documentary Paris Is Burning (1990). The film chronicles the 1980s Ball scene in New York City, wherein disenfranchised queer youths created a community structured around family-models known as Houses (composed of Drag mothers and their broods of drag daughters). The Houses engaged in friendly competitions with one another, known as Balls, where entrants competed to create the most ‘real’ or authentic mimesis of esoteric categories of female impersonation and masculinity (ranging from ‘executive realness,’ to ‘banjee boy realness’ and every other ‘realness’ in between). In this tradition, Olympia and Godzilla included one walk-off competition per night, however, in order to ensure they were creating a supportive drag environment any rivalrous connotations were de-emphasised; “we didn’t want to have an intensely competitive element to it.”

The highlight of the night is the showcase of two or three drag performers, where “we rotate that around to try to give new people their first exposure, and to get people we think are amazing back.”

Anyone who is interested is generally welcome to perform, and Taylor encourages newcomers to speak up in this regard. “I think people are really scared of asking for gigs, and people really should—if you want something, ask for it.”

In this spirit, entry is cheaper for those who dress up.“The idea is to get as many people to dress up as possible, and get people who come to the party who are really inspired by that to perform.”

“We don’t make much money at all, it’s just about doing something that we love, and part of that is inspiring people to do the same thing that we love doing.”

While this project revolves around welcoming newcomers to drag, the medium is something that Taylor has always been interested in on some level, since childhood. “I was a lot more fascinated with dresses than I was with anything else,” Taylor says, “with all sorts of feminine things.”

“When I first heard about reincarnation I thought about I’d been reincarnated wrong, as a boy, and that I was supposed to be a girl.”

Taylor’s original interest was not so rigidly tied to gender, but rather to an interest in aesthetic properties which have been attributed to the female gender role. “I was into things that were long and flowing, and far more often that would likely to be things like dresses than it is to be pants and t-shirts.”

This interest translated to Taylor using drag for costumes at dress-up parties, and for going out. The first few personas created were proportionate to this purpose; “there was Babs, and Camille, but they were very short-lived.”

These forays were noticed by a friend who was running a queer night, who asked Taylor to do a performance at a party, “and then I did it and then just didn’t stop.”

This is where Taylor’s first incarnation as a drag queen, Mummy Complex, emerged.

Mummy Complex’s first drag show was with Godzilla, at a night called Truckstop Cock Monsters that was at the Old Bar in Fitzroy. The show, called The Pashing of the Christ, and was an “erotic love story between the Virgin Mary and Jesus.”

Taylor performed as Mummy Complex for three years before becoming Olympia Bukkakis.

While Mummy Complex was more of a drunken extension of Taylor’s own personality, with a more amplified, irreverent brand of facetious wit, Olympia was an altogether different character.

“Olympia is more grand, overbearing, and also disgusting, than Taylor.”

“I think one of the things about drag is that you get to break social rules, and it’s kind of a measure of your character, how moral and kind you stay in relation to that,” Taylor says. “You can be quite mean; it can change you.”

Part of the challenge in drag is maintaining one’s personal politics. “Because of my childhood experience, remembering really wanting to be a woman, actually having some sort of curiosity about the feminine experience, a lot of my earlier shows had really clunky obvious feminist themes to them,” Taylor says. “I would be saying, this is not a parody of women but if anything, it’s a tribute.”

While Taylor used to feel that it was necessary to overtly justify using the performance style, Olympia’s performances are now left to speak for themselves (“I don’t think it doesn’t necessarily need justification as to how it relates to people who are women.”)

Taylor’s politics have become more implicit, and are applied in an everyday sense. “On a microphone (at a club) I wouldn’t make an immature joke to the crowd about women’s vaginas, in the same way that I wouldn’t tell that same joke sitting around with my friends.”

However, Taylor appreciates the capacity for political conversation proffered through the medium, as if “if you’re a performer and you’re a host, and you’re constantly communicating often one-way with a large group of people, that’s quite a good opportunity to communicate your ideas.”

“Just the same as any kind of performer, you can make political points,” Taylor says. And when making jokes, or points, “I try to make responsible ones.”

Olympia’s aesthetic is not the easiest to define. ”I don’t really like the term alternative drag, or alt-drag, because it’s an alternative to what? If that’s what you’re doing it’s not an alternative is it? It’s the centre of your universe.”

“I like messy drag, trash drag, or something like that.”

Olympia’s look is generally built out of one of two divergent models; that of a “beautiful woman with some kind of unsettling element”, (“I just never go for the beautiful drag queen look because I’m not inspired by it at all.”) or that of a “monster”.

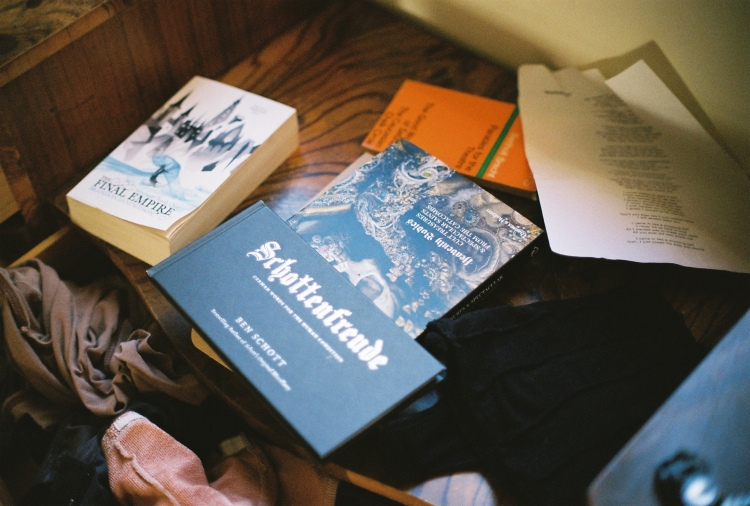

Olympia’s costumes are mainly sourced from op shops and on the street. “I don’t spend a lot of money on costumes but I still manage to find decent ones.”

“With clothes I learned early on, you always keep an eye out for something in an op shop which you could wear that would be amazing.”

Olympia also occasionally borrows costumes from friends. Recently, when she appeared at the queer Melbourne festival, Midsumma, she wore a borrowed velour Juicy Couture tracksuit. She was caked orange with fake tan, had bleached hair and pitch-black roots, and smeared garish blue eyeshadow on her lids to top the look off.

And because she never had a drag mother she did not have traditional makeup fundamentals passed down to her.

“There’s a big divide between the north and the south of the Yarra (river) and because there wasn’t much drag north of the Yarra when I started I didn’t have a drag mother so I taught myself, and learned from friends who were starting at the same time as me.”

She also learned, in true Gen-Y fashion, from Youtube tutorials (“Manila Luzon has as really good one.”)

Makeup preparation forms part of the ritual for both the physical and character transition that occurs between Taylor and Olympia, and other dramatic characters.

“The process of doing the makeup really is the process of becoming that person,” Taylor says. “You’re looking in the mirror and you’re seeing a literal physical transition.”

“I guess it’s quite difficult for your mind not to follow, too.”

There is something about the ritual, which is “comforting” and which helps to alleviate some of the anxiety that comes from the transgressive nature of the performance style.

“When you start out, you know that you’re breaking some rules there; any sort of comfort that you can give to yourself is a good idea.”

The process and the hierarchy of applying makeup helps to form a structure for the ritual; as “you put on something that’s a cream base and then you put powder on top, layer after layer after layer.”

“it’s comforting because it’s like painting, it’s like painting a house or something—I think that’s the same for a lot of queens.”

Taylor’s relationship to makeup, however is quite complicated, due to not coming from an artistic background, like a lot of other queens do.

“I’ve always had a complex relationship to makeup because I was never good at drawing,” Taylor says. “A lot of my friends who do drag when they do makeup they can build on the skills that they had when they were good drawers or good painters as teenagers.”

“I had to start from scratch and I found it really difficult.” Never having learned about makeup from a mother, or younger sister, Taylor has rather embraced it for the purposes of drag.

“It’s nice, and I’m really proud of the fact that I have the ability to change my face.”

Makeup, however, is not that interesting to Taylor, in and of itself.

“Makeup has always been a means to an end for me; I love makeup because of what it means.”

Olympia performs both as an individual drag artist, and as a host, and has different methodologies of preparation for each performance style. For a show, Olympia will usually present a fully realised, usually ten-minute set, interlacing lip-syncing, pop-cultural references and comedy. In preparation, “I come up with that idea, often through listening to a song on my iPhone, and then a basic joke idea will come to me, and then I’ll play it over and over and over and then I’ll spend a couple of hours, over a couple of days rehearsing over that.”

Due to the level of rehearsal required she charges at least $100 for a ten minute show; (“there is more than ten hours of work that will go into each of them”).

Olympia also hosts drag shows, where she will introduce the performers and perform a monologue, and these gigs have a more improvisational quality.

“If there’s a theme to the event I’ll talk about it with my friends, and if I say something that’s funny, I’ll try to say that.”

“If I’m introducing a show there’s generally like one or two jokes that I’ll put in before I start the show,” she says. “It depends on the sort of thing, if it’s just hosting generally I’ll just make it up on the spot.”

But, Taylor admits, “It’s a lot easier if I’ve had one or two drinks.”

While this style of drag performances make up the bread and butter of Olympia’s work, she has also had several forays into dramatic acting.

Taylor was also the drama kid in school but didn’t act again until Olympia began performing with the Sisters Grimm in 2010. The Sisters Grimm is a queer theatre company based out of Melbourne, who were founded in 2006 and have since (according to their Facebook page): ‘been making theatre that is cheap, accessible, and extremely faggy’.

He met the company’s founders, Declan Greene and Ash Flanders through being out and about, “young gay and drunk.” After Declan started dating a close friend of Taylor’s, they started hanging out more.

“Then I saw their a show that had been written in two days or something like that, rehearsed in one day, and it was this amazing mess, called When Lorraine Stops Falling.”

When completing a Bachelor degree at Melbourne University, Taylor undertook a subject on performance art, and learned about Forced Entertainment—a performance group based out of Sheffield in England—whose performances in the 1980s pushed the boundaries of what constituted entertainment, and which relished in the implicit failures and loss of control at the borders of performance.

“That made me really obsessed with ruptures in performance, which is something that I really love in what I do— when something fucks up and then I’m standing there naked in front of a crowd.”

“But with that play it was just amazing, there were so many moments of incredible intimacy and it was also one of the funniest things I’d ever seen.”

At the end of the show Taylor approached Declan and Ash and gushed about how incredible the show had been and they invited Mummy Complex to perform in one of their future productions, The Rimming Club, which they performed at the This Is Not Art festival in 2010.

“I got to sing Amazing Grace and put rocks in my bra in this quasi-Virginia Woolf suicide attempt, it was great.”

After that they wrote a part for Mummy in their production, Summertime in the Garden of Eden, of Honey Sue Washington. In the play, set in Civil War Georgia, all the female roles were played by drag queens. The play was an overwrought melodrama of the camp-eth degree, peppered with homages to Gone with the Wind and tributes to Tennessee Williams, and underpinned with a savage satire of heteronormative politics and patriarchal stereotypes. Their first performance season was set modestly in the garage of a share-house in Thornbury, before a reprisal season last year, where they performed at Theatre Works in Melbourne and at Sydney’s Griffin Theatre. The production, rather than being improvised and messy like the shorter productions by the Sisters, had a structured, and time-consuming rehearsal schedule.

“For a drag queen who’s used to rehearsing for a couple of hours, it was long and rigorous,” she says, with a plodding emphasis.

However,Taylor found it to be an extremely gratifying experience, which both tested and advanced his skills as an actor, as well as a drag queen.

“When you’re a drag queen performing in clubs it’s all over in a heartbeat, and everyone who watched it was drunk,” she says, admitting, “you shouldn’t but you can get sloppy on details.”

“Because my character has a breakdown at the end of the play, learning how to call emotion up, express it, and then put it away at the end of the scene, or at the end of the rehearsal, became a really necessary skill.”

“All I did was try to remember the time in my life when I was most broken, and to remember that and sort of feel that, and then forgot that and think about the script, but try to keep that going for a bit,” she says, “but then I didn’t think of how to let that go.”

“It was quite a difficult skill to learn to put that emotion away.”

This is where Taylor benefited from working with a team of more experienced performers skilled in a dramatic acting and being able to “pick their brains”. (“I was able to ask them, how do I deal with this? And how do I do this? And that was really cool.”)

This has also enhanced the precision of Olympia’s other performances.

“I feel like I’ve become a lot better since that play, and I think part of it is because I have that practical acting training now.”

“If there’s a moment in a show that really calls for a really sincere expression, I have a bit more subtlety now.”

“If I should be happy but a little bit more nostalgic at a point of the five-minute show, then I don’t just do an exaggerated thing, I can be a bit more nuanced.”

“There’s more possibilities when you’re doing a show in that sort of way,” Taylor says, adding thoughtfully, “you can say a lot more things if you’re using a finer point. “

While most of Olympia Bukkakis’s drag performances have been in Melbourne, recently Taylor has been living in Berlin. In the last few months of living there before returning here Olympia had begun performing, which led to one of her most memorable moments. Olympia had got her friend to DJ in true Berlin fashion “in an renovated old mansion,” turned club called Chalet. “He was DJing for an hour and I would just perform whenever I felt like it.”

“It was six a.m, and it was the biggest point of the party and everyone was really wasted.” Taylor got his friend to play a song, (“just because I wanted to hear it”) and started dancing on the wall at the side.

“People started watching me and I decided, oh I guess I’ll do a performance to this.”

“I got everyone to get down of the ground on their knees, all these Berlin hipsters, and to wave their arms above their heads, and then I stood up and got everyone to wave their arms toward me.”

“I was in this ocean of waving arms, really, really wasted, and I made eye contact with this guy who was standing at the edge of the dance floor, and just mouthed the words, ‘I know,’ because we were just like, I can’t believe this is happening.”

“That was pretty amazing.”

The local drag scene there is quite distinct from the expat scene Olympia has recently become part of. “German drag: I didn’t quite get it, there’s a bit of a cultural disconnect there.”

“I really liked all of the expat drag queens, there was ones who do femme realness, who look like stunning, really fashionable, hipster women, and they’re lovely, and there’s one who does amazing punk sort of drag.”

However, getting people involved with the scene and with the idea of dressing up, at all, in the first place, is challenging in Berlin.

“People in Berlin don’t dress up as much as people do here, and people aren’t as willing to do it,” Taylor says. This resistance is not only embodied by those who are image aware, but also by more threatening objectors.

Berlin, Taylor says, is more of a “real city” than Melbourne. “I was threatened by Nazis three times while I was there; it can be really intense.”

“Neukölln, the place where people hang out can be a bit dangerous,” Taylor says. “There is more of a threat of homophobic and transphobic violence.”

Performing in a city which is more resistant to drag is an important symbolic act, but Taylor enjoys performing more in somewhere like Melbourne, where it is embraced by a wider group of people; (”It’s kind of more inspiring if everyone’s getting into it.”)

“Doing drag or at least dressing up wildly, and dressing up as things that are held to be unusual or wrong, if it’s just you alone it can be a bit harder.”

“I guess because I started out with a group of friends that didn’t have any mentors, then that means that any time that I feel like if I’m ever surrounded by a big family, I get quite inspired.”

This is one factor that makes Taylor the most proud of Pandora’s Box. “A lot of people did do drag for the first time at Pandora’s Box, and a lot of people started doing drag at Pandora’s Box, which I’m really proud of.”

Taylor also embraces the mainstreaming of drag through television programs such as RuPaul’s Drag Race, a game-show/reality show hybrid hosted by the quintessential model for commercial drag queen success herself, RuPaul.

“I think it’s good for us to be able to see ourselves on screen; whether it’s being queer, or being a drag performer, or being transgender, it’s really nice to see a representation of yourself in the media, it’s nice to see some sort of proof that you exist in that.”

“But it’s the same with any other sort of fringe art, the more something comes into the mainstream, and the more something is popularly understood, the more it’s going to have to follow a certain set of rules.”

Rupaul espouses the value in pushing the drag star to her limits, popularising (and often over-using) catch phrases like “You’d better work,” and the more brutal; “Don’t fuck it up.” This ethos includes her frequent encouragement (or badgering) of more experimental and avant-garde drag queens do ‘fish,’ (the quintessential feminine drag look), an idea which it has taken Taylor a long time to relate to.

“I think while I think it is important that if you want to be a drag performer, or just a drag queen, if you’re going to do that you need to really push yourself, and that’s something that I really didn’t do in the first couple of years that I was doing it.”

“I think it’s good to learn a rule so then you can break it artfully,” Taylor says. “To learn how to do pretty things, so that you can do something that’s pretty in a new way, or beautifully ugly.”

“It’s easier to look like a busted amazing weirdo than to look flawless.”

However, Taylor does see the drag represented on the show as fairly limited in its scope.

While “there are as many ways to do drag as there are people,” the show represents a fairly narrow definition of the craft.

And thus, despite Taylor’s interest in the hard-work ethic encouraged through the show, she is less interested in its aesthetics. “There’s things like the East London drag scene which is very wild, and messy, I think that’s much more what I’m interested in than like an American pageant sort of thing. “

Taylor is similarly very open to the idea of cis-gender heterosexual females and males engaging with drag. “I’m so for it. I think it’s great.”

“I’m thinking in particular of a straight guy that I know who’s really into drag, and he dresses up and does it, and I just think that that’s the most beautiful thing in the world,” Taylor says. “Sometimes you look at things and they’re just so beautifully modern,” adding, “and there’s obviously a really big different between that and a bunch of really idiotic football guys wearing tutus at their awards night.”

“And I still do think it is cross-dressing for a woman to do drag as well, to do drag, F-to-F, I think that can be just as liberating as well.”

Taylor is particularly fond of Sydney based F-to-F drag queen, Betty Grumble, whose look is “incredible.”

“I think the only differentiating factor should be how talented or how kind someone is,” Taylor says. “So it’s best to just forget that stuff, about from where you’re coming to your character. Obviously the character is the most important part. “

“I think the more the merrier, and the more that it means to everyone the merrier as well.”

While Taylor sees these developments in drag as strikingly current, he can not visualise the future so clearly. ”I try to think about that and it’s just blank,” Taylor says, honestly. “What I would like to do is to stay interesting and keep progressing, like, whatever direction that is.”

“Ash Flanders (who co-wrote Summertime in the Garden of Eden) once asked me, did you ever worry, Taylor, when you were a teenager and started doing drag whether you would end up being the bogan in a dress standing saying, ‘5 dollar cock-sucking cowboys at the bar for the next five minutes’?”

“I hope that it continues to be art rather than work for me, although both of them are great.”

“I’d rather not be wearing a dress to sell cock-sucking cowboys,” she says, breaking into laughter.

And while, like most drag queens, she can never resist a punchline, Olympia Bukkakis is nonetheless a woman very serious about her art.

You can see Olympia’s Facebook page here, find out about future Pandora’s Box events here, and learn more about the Sisters Grimm on their website.